Fake Emails & Small Businesses

Summary

In 2021, it really shouldn’t happen where emails are forged, or spoofed, with spam or malicious emails made to look as if they come from your company, e.g. me@mycompany.com. Unfortunately, there are plenty of improperly configured email domains which are not secured and hence become an attack vector for bad actors to attack your business.

The good news is, it can be fixed. Better yet, it can be proactively headed off before it becomes a problem in the face of your business.

In this article, Thomas Carlisle will give you a deep dive into email and domain security. Thomas has over 25 years as a professional IT expert, having worked for or consulted to hundreds of the biggest corporations in the world.

Hang On: You Said a Strange Word…What is an Attack Vector?

“Attack Vector” is an IT security buzzword which simply means something an attacker can use to attack your business. While we’re on the topic, “Attack Surface” means “thing” — networks servers, and any service running on them) which could potentially be used to probe and find vulnerabilities, which then become an attack vector.

On a side note, if you want to speak in IT security circles, you really have to make sure you use the words “Attack Surface” and “Attack Vector” at least three times per hour. It’s a rule.

How Can My Email Domain Be Used to Carry Out Attacks On My Business?

Well, imagine if attackers were to break into your email system so they can actually send messages which appear to be from you. That would be really, really bad, right? The damage they could do is virtually limitless.

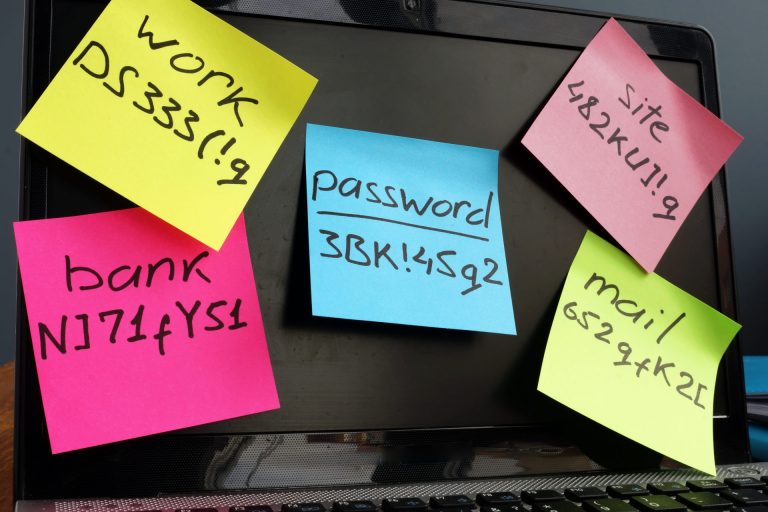

But, your email servers are properly secured and your email users practice good password hygiene, so attackers are not going to get into your email system.

But here’s the thing….. they don’t necessarily have to. The next best thing is if they can send emails making it look like they come from you, then that is almost as good as actually breaking into your mailbox.

Moreover, if they can send as anyone in your email domain, e.g. @mycompany.com, then they don’t have to break into multiple mailboxes. We call this email spoofing.

Examples of Ways Your Business Can Be Harmed by Spoofed Emails

There are many ways that spoofed emails can be used to attack your business. The formal term for attacking via email is “Business Email Compromise”, which we abbreviate as BEC.

Spoofed emails are just one form of BEC, and what we are talking about here. Here are just a few ways that spoofed emails can harm your business:

- Attackers can damage your company’s image and reputation.

- Attackers can send bulk spam from your domain, which will get your domain blacklisted from email servers around the world.

- Attackers can get your business suspended from google business, and other important business directories, by sending spam and/or malicious emails as being FROM: your domain.

- Attackers can carry out phishing attacks. Phishing is sending emails trying to gain the trust of someone to get them to do something they wouldn’t do unless that trust was there. For example, clicking on a link in the phishing email, etc.

One of the most creative attacks I have seen recently is a case where upon discovering an insecure email domain, the first the attackers did was send an email from someone@yourcompany.com and lay out a ransom.

The attacker claimed to have complete control of the company’s systems, and hence could do whatever they want, and demanded a ransom be sent and they provided a Bitcoin wallet.

Moreover, in that ransom, they explained they already had taken control of the camera on that person’s computer and had videos of them perusing adult websites and doing a Jeffrey Toobin. I am not going to describe further details on that.

But it was quite creative and potentially effective. Because they were threatening to circulate that video if the ransom wasn’t paid, as well as to shut down their company’s IT systems.

The only kicker is, they didn’t actually have access to do any of those things. But as long as they can make the target company believe they had that control, that becomes to motivator to pay the ransom.

Luckily, instead of paying that ransom, the company owner contacted me instead. I was able to quickly determine the attacker did not actually have access and instead was spoofing from that company’s email domain.

Here is a snippet from that ransom email:

“All you have to do to prevent this from happening is – transfer bitcoins worth $1450 (USD) to my Bitcoin address (if you have no idea how to do this, you can open your browser and simply search: “Buy Bitcoin”).

Actual Ransom Email

My bitcoin address (BTC Wallet) is: 1D8qdtNLNbvugZyMYUyhzcGiCdFinxHgtH

After receiving a confirmation of your payment, I will delete the video right away, and that’s it, you will never hear from me again.

You have 2 days (48 hours) to complete this transaction.”

How do You Determine if an Email Ransom is being Spoofed?

Unfortunately, you can’t tell by looking at the email in the way you read emails through your email app. To check the authenticity of an email, you have to look at the “mail headers”, or “show original”. Virtually every email client will have these features, but they are not easy to find.

In Gmail, you open the message and then click the “three dots” button to see more options, and “View Original” is one of the options.

Also, if the email is forwarded, that doesn’t work because the header information you see is not the header for how the ransom email got into the person’s mailbox, instead, you are looking at the headers on the message being forwarded.

You have to have access to the original message, but before we get into that, I need to make a key point.

Spoofed Emails Do Not Flow Through Your Mail Servers… At All

This means you can’t filter them out. What? This is an important key point. A forged email gets sent from the attacker’s system, directly to some other email system and never touches your mail system.

Thus, you have no way of knowing it is happening, and there is nothing you can do to filter it on your mail system.

The only way my recent client knew their business was the target of spoof email attacks, is because the attacker forged an email from that company, and also to someone at that company — the ransom email.

Unless they send you a ransom, you don’t know it is happening. But other mail servers around the world are receiving emails claiming to be from @yourcompany.com….. even though they did not.

But fear not, because although you can’t control or filter spoofed emails from arriving at mail servers around the world, you can do some things which other mail systems around the world will do to determine if emails addressed are actually coming from your mail system.

It is easiest to talk about the things you can do by looking at a legitimate email header.

What Headers Look Like on a Legitimate Email

Here is an example of email headers on a legitimate email. This is the client forwarding the ransom to me, which as I said does not tell you how the original message made it onto the client’s mail system. I have redacted my company’s server names, etc as: me@mycompany.com is me. Note, you don’t have to digest and understand this thing. I’m going to break it down in pieces, but first here is a mail header:

Delivered-To: xxxxxxxxxx@gmail.com

Received: by 2002:a17:907:784e:0:0:0:0 with SMTP id lb14csp1385307ejc;

Thu, 16 Sep 2021 10:13:25 -0700 (PDT)

X-Google-Smtp-Source: ABdhPJwXIoIaQnUk+y2GREPJeT21IDaP42ibxJDISuNQQAz1p8LGzO2tg13RBGOKLCmNKyEE5H2q

X-Received: by 2002:a05:620a:2988:: with SMTP id r8mr5986932qkp.445.1631812405260;

Thu, 16 Sep 2021 10:13:25 -0700 (PDT)

ARC-Seal: i=1; a=rsa-sha256; t=1631812405; cv=none;

d=google.com; s=arc-20160816;

b=nEW0Dq9Xp1RTmwUHF/jPmA7ZTHqi6Q9hqsna4sOGL//x/SFxBeEkhNf2EAWcw6EkP3

AAJK4YcP0gfUlBOrdJC7ziGf7nwfPbSJYxvYGgrfDJydbc9zN7gtdQDan2T7KTdIxNrU

KlfukNdUzVwjRJlgR5mfAPW8G80BkMXlqWnJ+WvSUiFrp+qO74V3ZKr+toIFb49XG1Lh

wvTNE44DVhwB0JEq1yakW0h/ojAz4a21GkwpA/J1D4j1AKF3lRTIrLWM9+3POV6SWjl3

+0rf074e9LUxl+vRMijpnoerAJh5119DFtlLjmQ/AeAgVzxFKtGVdAxo60H6Asw6BkIK

qoiA==

ARC-Message-Signature: i=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed; d=google.com; s=arc-20160816;

h=mime-version:feedback-id:list-unsubscribe:message-id:to:subject

:reply-to:from:date:dkim-signature:dkim-signature;

bh=/rzZ74hzL7rbo755mPGgdl+SgdEiMDsmnU3bPRmC3qI=;

b=JN3mJz4gkpaC79s0TDvVdLtmyN9UpUSQtmgkkyqVWH+3uDp+ff2ei7mZmdDzzY0x0Q

Z6FOMQHTyOrhAMrO0DcQdGGCBOyTVRnH5omlJqB8id24rp10qV40XI3XGfPWNAPFcRD4

XothGqVL9TqfKkG/Cw+0y2v6r4Jt54GpeEPwgRS1smmCIWNJYhYcqv0UZV2vK/gDjAQM

4KR7N5Pht87hLRBaHZh8NRnmV/IG1GustvqdZm0LAGehQ1vYj+JiN4xl7pHErLWhgWvu

Kd8+xspUQjidPDIO9g2urUxeyRB51l+K+6v+vwy7KmZFayp2nLldzfZMxEmFcps8dUQG

gy3g==

ARC-Authentication-Results: i=1; mx.google.com;

dkim=pass header.i=@vmug.com header.s=informz1 header.b=tt7bFr3K;

dkim=pass header.i=@informz.net header.s=testip header.b="aURx/vZO";

spf=pass (google.com: domain of nde_7571012117.4@informz.net designates 205.201.41.208 as permitted sender) smtp.mailfrom=nde_7571012117.4@informz.net

Return-Path: nde_7571012117.4@informz.net

Received: from mail.41.208.informz.net (mail.41.208.informz.net. [205.201.41.208])

by mx.google.com with ESMTPS id h7si1912198vsf.196.2021.09.16.10.13.24

for xxxxx@gmail.com

(version=TLS1_3 cipher=TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384 bits=256/256);

Thu, 16 Sep 2021 10:13:25 -0700 (PDT)

Received-SPF: pass (google.com: domain of nde_7571012117.4@informz.net designates 205.201.41.208 as permitted sender) client-ip=205.201.41.208;

Authentication-Results: mx.google.com;

dkim=pass header.i=@vmug.com header.s=informz1 header.b=tt7bFr3K;

dkim=pass header.i=@informz.net header.s=testip header.b="aURx/vZO";

spf=pass (google.com: domain of nde_7571012117.4@informz.net designates 205.201.41.208 as permitted sender) smtp.mailfrom=nde_7571012117.4@informz.net

DKIM-Signature: v=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed; s=informz1; d=vmug.com; h=Date:From:Reply-To:Subject:To:Message-ID:List-Unsubscribe:Feedback-ID: MIME-Version:Content-Type; i=memberservices@vmug.com; bh=/rzZ74hzL7rbo755mPGgdl+SgdEiMDsmnU3bPRmC3qI=; b=tt7bFr3KLnbL2aGx8hfXNRk/k+XPhttVFXo+3Vk4ulyXCBCBP2iuK7nK3T02JARXPmr5x/5MGWHl

lNGlnAP2VAQxguU7w5VDMUQ44ELoHv5gNHnxJkjlRmckjC4FVOATMrwH+4NX4ZL39B72tyUD7i/v

Gs8j8pBv1dcOr926HzY=

DKIM-Signature: v=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed; s=testip; d=informz.net; h=Date:From:Reply-To:Subject:To:Message-ID:List-Unsubscribe:Feedback-ID: MIME-Version:Content-Type; bh=/rzZ74hzL7rbo755mPGgdl+SgdEiMDsmnU3bPRmC3qI=; b=aURx/vZOVL6/7rTJJolfOGYHPFOJYrPJHl9YwXIpnyC1cyH5InkX3cfcZooUZr0ug9Xe1VgHJO6N

7ZqtbMfruy1RdB3Qds7XT+qsBXvY4WGVoJjmdLNSVokhrnO/jdGNyJ2enYIXYwqmpOsIyDHPPnMb

Ax3lKQTj2p+nYSutVyw=

Received: by mail.41.208.informz.net id h8dtj82t3mo0 for xxxxx@gmail.com; Thu, 16 Sep 2021 13:07:53 -0400 (envelope-from nde_7571012117.4@informz.net)

X-Receiver: xxxxx@gmail.com

X-Sender: nde_7571012117.4@informz.net

Date: Thu, 16 Sep 2021 17:07:49 -0000

From: VMUG memberservices@vmug.com

Reply-To: memberservices@vmug.com

Subject: Who's Excited to Get the Band Back Together at VMworld 2021?

To: tcarlisle2012@gmail.com

Message-ID: 7571012117.4@informz.net

Feedback-ID: 40492:10217406:205.201.41.208:informz.net

MIME-Version: 1.0

Content-Type: multipart/alternative; boundary="NDE0MDAxMzk5OTkzNDMwNzcw"There are three things I look at in this mail header to determine it is authentic and came from shutterfly.com. More importantly, my company mail server looked at these same three things to determine if it should allow the email to come into my mail system.

Those three things are DKIM, SPF, and DMARC.

Ok, you caught me, only two of those things are in this mail header: DKIM and SPF. Let’s talk about that before we talk about DMARC and why it isn’t in this particular mail header.

DKIM: Domain Keys Identified Mail… Prevents Message Header from Being Altered.

DKIM is a standard which all legitimate email systems follow. Because message authenticity is determined by the mail headers, it makes sense that the mail headers have to be impossible to alter…. or fake.

DKIM is an encryption scheme that mail system use, which makes it impossible to alter mail headers. It is a public key encryption method, which means that there are two parts to the encryption:

- The mail system(s) which legitimately sends emails for an email domain will sign message headers with a private key.

- All other legitimate email systems decrypt mail headers using the public key for that company’s email domain.

The important point is in a public/private encryption scheme, your system knows the private key and uses it to encrypt, and other systems look up your public key to decrypt the mail headers.

The net result is, if they can decrypt the mail headers using your company’s public key, then DKIM passes. If they cannot decrypt the mail headers using your domain’s public key, DKIM fails and the mail system throws the message away.

Where Do Other Mail Servers Get My DKIM Public Key?

That is a fair question because for DKIM to work your public key needs to be published somewhere. Where is that?

Well, it turns out that DKIM public keys are published in your company’s DNS. This makes sense because:

- DNS lookups are fast and easy to do

- Only you, or legitimate people from your company, can edit your company’s DNS.

So it makes sense to stick the DKIM public key in your DNS. From the mail header I used above, here is how this mail header tells mail servers where to get the DKIM public key:

DKIM-Signature: v=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed; s=testip; d=informz.net; h=Date:From:Reply-To:Subject:To:Message-ID:List-Unsubscribe:Feedback-ID: MIME-Version:Content-Type; bh=/rzZ74hzL7rbo755mPGgdl+SgdEiMDsmnU3bPRmC3qI=; b=aURx/vZOVL6/7rTJJolfOGYHPFOJYrPJHl9YwXIpnyC1cyH5InkX3cfcZooUZr0ug9Xe1VgHJO6N

DKIM in Mail Header

7ZqtbMfruy1RdB3Qds7XT+qsBXvY4WGVoJjmdLNSVokhrnO/jdGNyJ2enYIXYwqmpOsIyDHPPnMb

Ax3lKQTj2p+nYSutVyw=

The DKIM signature includes a selector, in this case, s=testip. From that, the mail server that is receiving this message will look up in DNS the domain of the sending email, and use the DKIM selector specified in the header, and from that, they get the public DKIM key.

Using that public key found in the sending domain’s DNS, they decrypt the header fields and compare the result to what is in the DKIM signature.

Note, we are simplifying here, and not writing a deep dive on DKIM. The key point is that DKIM allows receiving mail systems to determine if the message is authentic, or has been modified and that the message really comes from the sending domain.

So the first thing one looks at in a mail header in determining the authenticity, is for a “DKIM pass”, and we see that literally in the sample mail header:

dkim=pass

In fact, we see two in the sample mail header. Why two? The sending mail system provided two DKIM signatures and therefore receiving systems use both, decrypt both, and both must pass.

Oops… I Just Said Something That is Wrong

Yes, it was wrong to say that receiving mail systems require that DKIM passes, or else the receiving mail server will throw it away. Why?

Because it shouldn’t be up to the receiving mail system to decide what checks must pass, and if not that the message should be thrown away (rejected).

Instead, the criteria on what checks have to pass need to be specified by the sending mail system. We will talk about that some more later.

Why is DKIM Alone Not Enough?

DKIM alone is not effective at preventing spoofed emails because of something called a “replay attack”. I am not going to go off on that tangent, and will just say that DKIM alone is just not enough.

By the way, “replay attack” is also a phrase that has to be in your everyday speak in IT security circles. It’s a rule.

Google GSuite & Workspaces Default DKIM is Not Enough

If you sign up to have your company’s email route to you through gsuite/workspaces, if you do not define a DKIM key Google will apply a default DKIM that they created to your outgoing emails.

This is not enough. In fact, it doesn’t even come close to being anything at all helpful. Why?

Because when someone is sending emails spoofed from your domain, they will be doing so on servers that they control. They won’t append that same DKIM, but other mail systems will not reject those spoofed emails because you have not told them to throw away emails from your domain if they do not have DKIM at all or if DKIM fails.

How Do I Tell Other Emails Systems to Throw Away Messages From My Domain If DKIM Is Missing or Fails?

No, you don’t have to pick up the phone and talk to all the email systems across the world. No, you don’t have to go on their websites.

You tell them that DKIM is required and that is must pass by publishing what is known as a DMARC record.

DMARC stands for Domain-Based Message Authentication Reporting and Conformance. You need to memorize that before you can take a modern email security certification exam. It’s a rule.

In a nutshell, DMARC is how you tell other email systems to reject emails addressed as from your domain unless DKIM passes. Well, technically, DMARC treats DKIM and SPF, which we haven’t talked about, combined. So it is time to talk about SPF.

SPF: Sender Policy Framework

Like DKIM, SPF is another standard designed to make spoofing emails extremely hard. Remember when we said DKIM was not enough, and I briefly said it was because of “replay attacks”?

SPF and DKIM together make replay attacks not possible. Let’s talk about how SPF works.

In order to prevent replay attacks, you have to make it impossible for anyone to stand up a mail server and send emails as being from your domain. SPF is the way we do that.

Think of SPF as a whitelist of servers that your domain says “these are the mail servers that can send emails as coming from my domain”.

It really is that simple, sort of. If you have one email server, then your SPF record will have one IP address. If every company had only one mail server with only one IP address, we could stop right here can call it a day.

As you know, we can’t do that. So what do we do, put a ton of IP addresses in our SPF whitelist? Well, yes…. sort of.

But before we start making a big whitelist, let’s talk about MX records and how that makes things more manageable. You set up MX record(s) so that other mail systems know your mail server(s) address(es) so they can route mail that is TO: someone@yourdomain.com to your mail server.

So it makes sense that you might want to tell SPF “allow all servers I have already designated with MX records to be whitelisted to send emails FROM: mydomain.com.”

And that is exactly what we do. A typical SPF record looks like this:

v=spf1 mx ip4:204.12.20.0/24 ip4:198.51.100.123 a -allWe aren’t going to deep dive here, and will simply explain what the above does:

v=spf1: is simply how all SPF records begin.

mx: means consider all my servers defined with MX records as valid servers to send mail from mydomain.

ip4: means allow this specific server IP (v4) to send emails from my domain. When you specify ip4: and give a subnet, as in the sample above, you are saying “all servers in this subnet of addresses are valid senders”.

the second ip4: is an example to show you can have more than one ip4:. You can have as many as you need (sort of).

a: means “any server whose fully qualified domain name (FQDN) is defined with an A RECORD in my domains DNS, should be allowed to send emails FROM: my domain.

-all: is the last thing in an SPF record, and it means “all” others. In this example, it means “if it isn’t a host in my MX record(s), isn’t in this subnet, or this specific IP address, and there is no A RECORD for it in my DNS, then REJECT IT.

The -all at the end is important. Note, it could be ~all. I’ll explain the difference:

-all means reject the message completely — it never hits anyone’s inbox. ~all means to mark it as suspicious. It still gets delivered, but may find its way into the spam folder.

Where Do I Publish My Domain’s SPF?

Yes, you must publish your SPF record(s) so that other email systems can find it and follow it.

Guess where that is stored? In your domain in DNS. Just like your DKIM is defined in your domain’s DNS, your SPF is also.

All the legitimate email servers in the world will know to look to your DNS to get your DKIM and your SPF, and they will follow what you have specified.

Let’s look at the sample mail header I gave earlier, and here are the SPF results in that mail header:

spf=pass (google.com: domain of nde_7571012117.4@informz.net designates 205.201.41.208 as permitted sender)

Here we see that SPF passed because the sending email domain’s DNS says that emails from that domain can come from the mail server that is trying to send it.

Before I talk about how to put your DKIM and your SPF in your domain’s DNS, let’s talk about DMARC.

DMARC: Best Practices for Preventing Email Spoofing

As a quick review, DKIM ensures the message isn’t alerted. SPF ensures the message only originates from mail servers the domain says are allowed.

So what does DMARC do? It does a few things, but most importantly it tells all the email servers in the world what to do if DKIM and SPF do not pass.

A simple DMARC record would be:

v=DMARC1; p=rejectThat simple DMARC record would tell all the email servers in the world “do not accept emails originating from my domain unless DKIM and SPF pass, and if they do not then reject the message”

You might have guessed already, that the DMARC record goes into your domain’s DNS also.

There are some other things DMARC can do, which I am not going to dive into. But remember when we said DMARC stands for “Domain Messaging Authentication Reporting and Conformance”?

Clearly, DKIM is the “authentication piece”, and “conformance” is the DMARC piece…. so what is “reporting”?

Reporting is also part of the DMARC standard. In your DMARC record, you can ask that other emails send you a digest of all emails they received, FROM: your domain, whether they passed/failed SPF and DKIM, and what the receiving mail server did (reject).

Here is what you add to get digests sent to your domain security team:

v=DMARC1; p=reject; rua=email-security@mycompany.com;These emails contain the source IP, the DKIM/SPF and disposition, and nothing more. In other words, not the names of the recipients, not the subject, and not the message contents.

There are other things that can go in a DMARC record, and while I am not going to cover them all I will show one that is going to useful to most small businesses:

v=DMARC1; p=reject; adkim=s; aspf=s; sp=reject; rua=mailto:dmarc-reports@mycompany.com; ruf=mailto:dmarc-reports@mycompany.com; fo=1;Here is what each of those command tags does:

- v=DMARC1 is simply how all DMARC records start

- p= reject means to reject emails if DKIM and SPF do not pass

- adkim=s is specifically how “strict” we want DKIM enforced, and the s means “strict”

- aspf=s is specifically how strictly we want SPF enforced, with s meaning “strict”

- sp=reject means “any mail server sending mail from a subdomain of mycompany.com should be rejected. If you do not put this, attackers can try to spoof emails from someone@mail.yourcompany.com, etc.

- the RUA and RUF tags specify where to send DMARC reports

- fo=1 means to send a report to the RUF address anytime either DKIM or SPF fails.

Putting It All Together: DKIM + SPF + DMARC

DKIM Setup

To create a DKIM record for your domain, you must generate the DKIM public/private key and it has to be in a specific format. The easiest way, and least error-prone way, is to generate your DKIM key pair using tools built specifically for this.

If you google search “DKIM generate” you will find a few sites that you can use. Note, whenever using a third-party site for something like this, always remember you are inherently trusting that site is not malicious or compromised.

This site: https://easydmarc.com/tools/dkim-record-generator is one.

In order to generate a DKIM you need three pieces: a selector, your domain name, and the desired encryption bit length.

The domain name is the domain name that you are aiming to protect. It is whatever comes after the @ symbol in someone@mydomain.com.

The bit length should be 2048. Do not choose 1024 because Google has already started rejecting DKIMs unless the length is 2048.

The “selector” is an identifier you pick. It can be whatever you like, but DKIM, default, etc. are good choices.

When you “submit” you will go to a screen with three pieces: the private key, the public key, and the DKIM Key.

DKIM DNS Record

The “DKIM Key” is the public key formatted exactly as you need to paste it into your DNS. Go to your DNS and defined a new record of type TXT.

The “hostname” should be the selector of your picker, followed by ._domainkey.

The “value” should be the DKIM Record you copied.

Here is a sample DKIM DNS entry if you chose “default” as the selector for the domain mydomain.com:

TYPE HOSTNAME VALUE

TXT default._domainkey v=DKIM1;t=s;p=MIIBIjANBgkqh...Note, I have shortened the DKIM key so it is readable. Obviously, you put the entire DKIM key in the “value” field.

How you do this specifically depends on what DNS provider you use to manage your DNS.

DKIM Private Key & Email Server Settings

The private key is what you must paste into your email server settings. Somewhere in your mail server, is a place to define a DKIM selector and put in your public key. Obviously, the selector is the same selector you defined.

If you use Google GSuite/Workspaces to handle email for your domain, you can find in the Admin web UI a place to set up your DKIM. You can generate the DKIM, and Google will automatically put the private key where it needs to go, and then give you the DKIM record that you put into your DNS.

Once the DKIM has been defined, put into DNS, and put into the mail server, DKIM is complete.

You can use tools to check DKIM and validate it, and you should.

SPF Setup

As we already discussed, DKIM alone isn’t enough. Luckily, defining your SPF isn’t quite as daunting of a task as DKIM was.

All you need to do is craft your SPF and put it into your DNS. Just like DKIM, it should be defined in your domain’s DNS as a TXT record type, the “hostname should be @, and the value should be your SPF record:

TYPE HOSTNAME VALUE

TXT @ v=spf1 mx ip4:123.45.67.123 ~allIf you use google or Microsoft outlook to handle your domain’s mail, or any third party, you need to put in their SPF include entries:

TXT @ v=spf1 mx ip4:123.45.67.123 include:spf.3rdparty.com ~allObviously, you need to put in the right “include” for whatever that third party is, and you need to put in the actual IP address of your mail server. (if it isn’t defined with an MS record, in that case, you can leave the ip4 tag out).

DMARC Setup

Your DMARC record also goes into DNS for your email domain, also as a TXT record type, with a “hostname” of “_dmarc”:

TYPE HOSTNAME VALUE

TXT _dmarc v=DMARC1; p=reject; adkim=s; aspf=s; sp=reject;

The above DMARC would result in legitimate email servers around the world rejecting emails FROM: your email domain unless the email is signed with your DKIM key, and comes from the IP addresses you defined in the SPF.

Validating Your Setup

The last step is, just as with anything in the IT world, easy to test and validate.

You can google search for online tools to check DKIM, SPF, and DMARC.

A good online tool is https://mxtoolbox.com/SuperTool.aspx

You can use MX Toolbox to query DKIM, SPF, and DMARC.

You can also use this site to test everything in one simple shot:

https://www.smartfense.com/en-us/tools/spoofcheck/

Using SmartFense, the expected output should be that the domain is not spoofable, and you can see the DKIM, SPF, and DMARC:

Not spoofable domain!

Found SPF record:

v=spf1 +mx +a ip4:216.137.187.246 -all

SPF record contains an All item: -all

Found DMARC record:

v=DMARC1; p=reject; adkim=s; aspf=s; rua=mailto:dmarc-reports@veteranstechgroup.com; ruf=mailto:dmarc-reports@veteranstechgroup.com; fo=1;

DMARC policy set to reject

Aggregate reports will be sent: mailto:dmarc-reports@veteranstechgroup.com

Forensics reports will be sent: mailto:dmarc-reports@veteranstechgroup.com

Spoofing not possible for veteranstechgroup.comTesting Email

Of course, you should also test email. You want to make sure that outbound and inbound email still works. You really should validate that when you send an email from your domain, it ends up in the recipient’s mailbox with the right headers that indicate DKIM, and SPF both passed and that DMARC was followed.

Just like in the example header which we discussed at the beginning of this article.

Summary

In this article, we talked about email spoofing and why it is important to prevent it, and how you can do that using DKIM, SPF, and DMARC. We talked in detail about those three things, with specific examples.

It is important to note, there is no “one size fits all” and the SPF and DMARC records we looked at are not going to be optimal in all cases.

DKIM, DMARC and SPF are complex with a lot of potential setup combinations. The examples in this article are the most basic, which will be what most small companies need.

Enterprises, and email service providers, have a much more complex setup.

Thomas is owner, proprietor, and chief consultant of Carlisle Technology Solutions. Thomas has over 35 years of experience in professional Information Technology solutions, possesses a strong entrepreneurial spirit, and has a skillset that spans all of IT.

Thomas has worked for, or consulted to, hundreds of Fortune 500 customers across financial services, pharmaceuticals, media, manufacturing, retail, automotive, defense, legal, accounting, and medical. Thomas has launched Carlisle Technology Solutions to bring enterprise-grade, cutting edge technology solutions to the small business owner.

Thomas lives in the United States with his wife and two children.

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing this post plus the rest of the website is very good.

Wow, wonderful blogg layout! How lonjg haqve you been boogging for?

yyou make blogging look easy. Thhe overasll lookk oof your

website is great, as well as tthe content!